Blog

Meet a Resident: Michele Bombardier

Michele Bombardier (’17), a speech-language pathologist from Bainbridge Island, began writing poetry in her youth before devoting herself to the form 15 years ago via a committed daily practice. Michele became part of the fabric at Mineral during her residency in August 2017. She went to the town church, invited the congregation of 15 to Mineral School’s residency reading (none came, but they did send her back to school with homemade muffins). She was spotted at Headquarters Tavern on the regular, reading Rilke with Jamison, neat. Board member and memoirist Putsata Reang (’17) spoke with Michele about Mineral, her work and publishing her first collection, What We Do (Aldrich Press, 2018).

How did you come to poetry?

I read a book when I was in my early 20s that accidentally completely changed my life. I read The Diaries of Etty Hillesum. She’s considered a grown-up Anne Frank. It’s during WWII. Her complete diaries were found. It’s in my bones this story. I was just out of grad school, newly married with my first job. I was beginning my life. I was reading the diaries of a woman who was also starting relationships; she was stepping into her world. Watching her go through exploring life as an adult and the horrors that are coming toward her, how she cultivates her interior life. At the end when she goes to the camps, she brings her journal and Rilke. She said, “We leave singing.” It was life-changing to read this. I have a fear of flying. I always read Rilke on airplanes. I want to die reading Rilke. I started reading Rumi and Hafiz, then started reading Denise Levertov, Marge Piercy, and Mary Oliver. I started reading women writing their lives and this blew me open to this idea that women could write their lives as poems and art and it’s beautiful, this struggling with balancing family life and interior life and who they are in the world.

You were a Mineral School resident in the summer of 2017. What did you work on while in residence?

I had just finished my MFA and it was exactly the boost I needed. I had three goals: write new work, organize my manuscript, and submit because I am a terrible sender-outer. I was shockingly productive at Mineral. (Michele, below left, was also very intrepid — there she is getting behind the wheel of a local fire truck.)

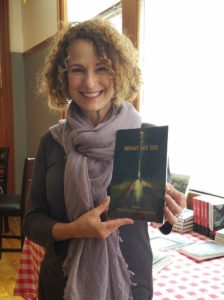

Post-residency, your first collection of poetry What We Do was published by Aldrich Press. Can you tell us a little more about your book, how it came to be, how many years it was in the making, what it was like to get that first e-mail (or phone call) expressing an interest in publishing your collection?

Post-residency, your first collection of poetry What We Do was published by Aldrich Press. Can you tell us a little more about your book, how it came to be, how many years it was in the making, what it was like to get that first e-mail (or phone call) expressing an interest in publishing your collection?

It has the skeleton from my MFA thesis fleshed out with both newer and older poems, so about seven years in the making, very Biblical. I was a finalist for a book a few months after residency but not picked as the winner, which was both thrilling and utterly devastating. Getting that firm “yes” email soon after that was a huge shock. I was home alone and I remember running up and down the stairs screaming and flapping.

How did you decide what poems to include?

With much agony and finally, with the input of my good friend and a superb poet, Gary Lilley. He reordered my manuscript and cut out about a dozen of my darlings. Great editor, that Gary. Also, one of my mentors was Joseph Millar who is genius. WWJD? “What would Joe do?” That’s how I make decisions. I need a bracelet.

The book, taken in its entirety, reads almost like memoir. There is a natural arc and progression of time, all pushing central themes of adversity, loss and fierce family love. Your father comes up often. Why is that?

The book is ultimately about redemption and compassion, how we adjust to loss and change. My relationship with him embodied this. My father was a complex, difficult, and violent man. He had deep wounds. The more I wrote about him, the more I understood him. In this way, poetry has been very healing. It fostered compassion as I explored family history, his WWII experience, and the stories and pain that were such a big part of how he was in the world.

The poem “My Grandmother Comes to Ellis Island: 1923,” which is your imagining of your grandmother’s first perceptions upon arrival in America, is one of my favorites. It’s heartbreaking and timely. She emigrated to America and left her baby behind, never to see him again—the kind of family fracturing that is a painful feature of the immigrant experience. What was the initial spark for this poem?

I’m interested in family fracturing and healing, especially when the healing takes more than one generation. I’m interested in how we carry trauma in our DNA, how we carry the stories of those who have gone before us literally in our bodies. In that way, we are all immigrants, slaves or refugees (unless we are Native American) as nearly every immigrant/slave/refugee carries trauma. I worry as a country we are losing our compassion, that we are losing sight of that. I’ve been researching my extended family and trying to write about each ancestor. My next book will have more of these stories.

In “Adherence: A Cycle of Sonnets,” you find inspiration in green grime at the bottom of the Mineral School toilets. That’s an unusual place to get inspired! Where else in an old school do you find inspiration?

Anything that catches my eye! I definitely write from a position of discovery: I don’t know what I will write about until I write it. Of that sonnet series, each sonnet took an entire day. I started with the last line of the previous sonnet. I hoped for a crown, but am happy with the four. I did not know I would explore spiritual struggle with the patriarchal paradigm until I was nearly done.

I collect words wherever I can if my writing is flat. I write every day but sometimes I just make word lists. I go to bookstores and look at titles. I love to just wander and see what image draws me, what words draw me. Sometimes I see a word I have to look up. Or a word and I like the taste of that word on my tongue. Those words often show up in my poems later.

What are you working on now and what should we be watching out for next?

I’m working on a translation of an Eastern European WWII poet who was a POW and wrote poems in his own blood. I will write poems in response, a poetic conversation across time and space, a project I’ve written a Fulbright application for and am waiting to hear back. I hope this will be my next book. I’ve started a social purpose organization, Fishplate Poetry that offers workshops and retreats while raising money for humanitarian aid, specifically Syrian refugees, which has been a blast. I may go to northern Iraq in Spring and teach a poetry workshop as well as parenting communication at a camp for survivors of the Yezidi genocide. I’m also working on starting a reading series on Bainbridge Island. That’s all. I’m a bit of an evangelist for poetry.

That’s Michele below with her residency-mates. From left to right: Olympia-based photographer Lou MacMillan, Michele, Putsata, and Seattle artist and poet Clare Johnson.